Why I borrowed a name from Salinger.

![]()

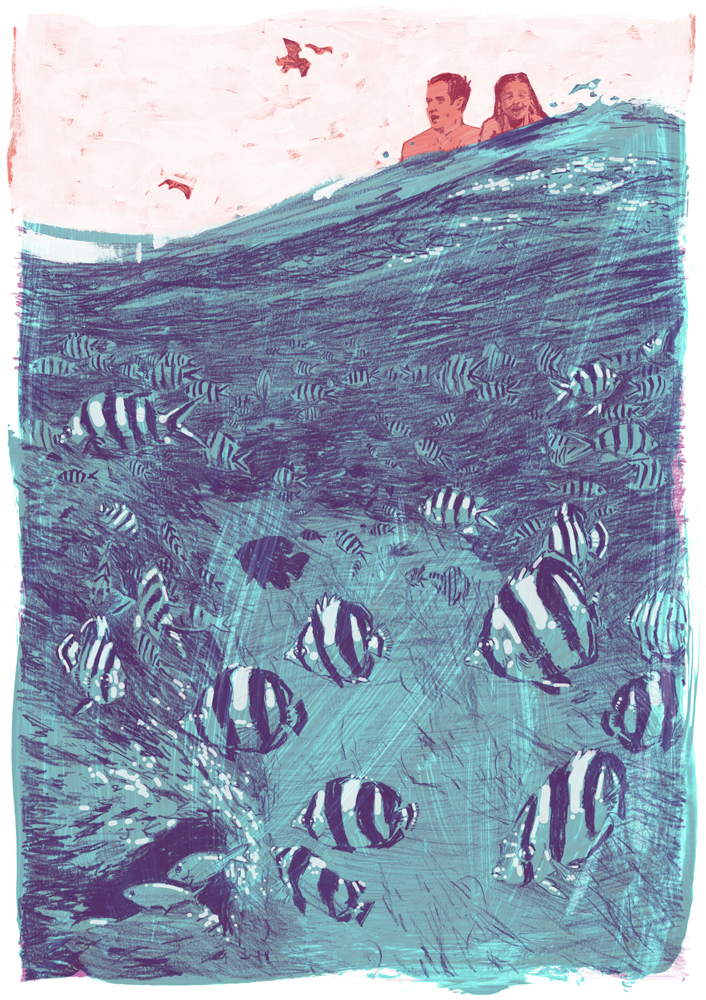

An illustration of Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” by Jonny Ruzzo, 2013.

Ask someone who Seymour Glass is and they’ll tell you he’s a Salinger character: the eldest of the precocious Glass family, a misanthrope who shoots himself on vacation in “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” But if that someone works in the New York fashion industry—specifically, in the editorial departments of select glossies—their response might be, Didn’t he used to work here?

That’s me they’re thinking of.

My birth name is Ricardo Rolando Hernández. When I was nine, as part of my so-called Confirmation into the Roman Catholic faith, an additional name—Jesús, naturally—wriggled its way between the Rolando and the Hernández, completing the inescapably Hispanic arrangement of syllables that would come to represent my identity crisis as a Cuban American.

Such a crisis was my birthright: Cuban people are defined by it. On the one hand, they take pride in the memory of an opulent tropical life before la revolución, a sun-bleached montage of salsa, palm trees, and café con leche amidst the palaces and sculptured colonnades of Old Havana. On the other, they feel shame for everything that happened after—deprivation, exile, and the loss of that former life, as they were forced to start over on to a different kind of island.

Unlike the rest of my uprooted family—we had ended up in Miami, as Cubans often do—my mother was born in the United States.

As a matter of pragmatism, she believed my Spanish name should be the single conciliatory nod to that “lesser” half of me, and introduced me to the cousin of a viewpoint endorsed by a certain Nick Carraway: Opportunities in America, like a sense of the fundamental decencies, were parceled out unequally at birth. And the better half of those opportunities went to rich white people—not to Latinos, and certainly not the progeny of Cuban exiles.

The resulting self-hatred ran deep, and my first hatred was my name. Another person might have found Ricardo Rolando Jesus Hernández to be a fine name—victorious and grand, a name in the tradition of the Spanish conquistadores. To me, it was a joke—that I should be saddled with a name like that, when all I wanted was to escape the inferiority that it denoted.

It felt like being forced to wear a painful pair of shoes, in a style I didn’t like. I knew I couldn’t change it—I was too young, and didn’t know how. But as I grew up, I started to realize, perhaps I could change other aspects of myself instead. This was the beginning of my interest in fashion: to change one’s clothes seemed a convenient alternative to changing one’s identity. I subscribed to Esquire; daftly attempted “layering” in the Miami weather. Then when I got into Yale, I made a weekly ritual of raiding the local New Haven thrift store for the hand-me-downs of WASPs: prep-school blazers, cable-knit cardigans, neckties embroidered with tiny whales and sailboats.

Fashion created a barrier between other people’s perception of me and my true self; allowed me to “pass” as another person—and by senior year, I wasn’t unlike the Pauper, bedecked in the Prince’s plumage yet possessing no royal blood.

I didn’t know what I’d do after graduation—just that I wanted it to involve art or fashion, and sweep me up into the glamorous blur of some life that had so far evaded me. This vague premise amassed a real shape when I landed an internship at a prestigious fashion magazine.

In anticipation of my first day, I had three custom suits made by a New Haven tailor, in opulent fabrics like shiny brocade and Oriental silk—the most expensive investment of my young life, and the beginnings of a new wardrobe. Around that time, I’d been reading Salinger’s Nine Stories, in which Seymour Glass makes his short-lived appearance. Wouldn’t it be fantastic, I remember thinking, to have a quaint old name like Seymour? To introduce yourself as a Seymour, thrusting out your palm for a handshake, would suggest not only that you were white, but that you were a hoity-toity kind of white, descended of old money and grand history. Maybe your family was Jewish, maybe French, maybe British—to be any of those was better than what I really was.

I looked into the process of changing one’s name. Evidently, it didn’t take much work—if you wanted a new name, all you had to do was begin using it. I knew I wanted to be a Seymour, but as I began to cycle through last names, I found that none was as appealing to me as Glass. For a fictional Jewish family assimilating to New York in the early twentieth century, the name Glass presented as much of a problem as my own name did to me in real life; for me, though, it seemed a poetic solution. I could hide in plain sight behind the gleaming sanctuary of a word like glass. I was attracted to the perfect symmetry—one shameful name erasing the shame of another, a bridge across decades, between fact and fiction, want and worth.

The transition was clumsy. The assistant who had interviewed me knew my real name—so did human resources—but even though I’d asked her to call me Seymour, she kept forgetting. When an important fashion editor spiraled into the office for the first time—a British dandy with a handlebar mustache, fresh from a vacation, yet roving like a lost whirligig—the assistant called me the wrong name, Ricardo.

The editor was patting around the towers of papers on his desk, in search of a misplaced scribble. “I thought your name was Seymour,” he said, referring to the name I had been using in my e-mails. I turned red—to disclose my name change stripped away the name’s power, defeated the purpose. He nodded abstractly at my explanation. Then he muttered something to his assistant about moth balls for his closet and was off once more, to catch a flight to a supermodel’s wedding in some improbable British shire. I spent the rest of the week confined to my desk, subsumed in dull work, my only opportunity for social interaction taking place over the cash register in the cafeteria.

It seemed I’d never get the chance to introduce myself to others—let alone reinvent myself—until another big-time editor showed up, also back from a vacation. He, too, was a dandyish character—larger than life, always sermonizing impressively about style and swooshing around in some glamorous mantle.

When we first met, he cast his eye over my Oriental suit, and flabbergasted, almost burst into amazed laughter: Who are you? he asked. I told him, and thereafter he made a habit of calling me into this office, to chitchat, and fix his computer.

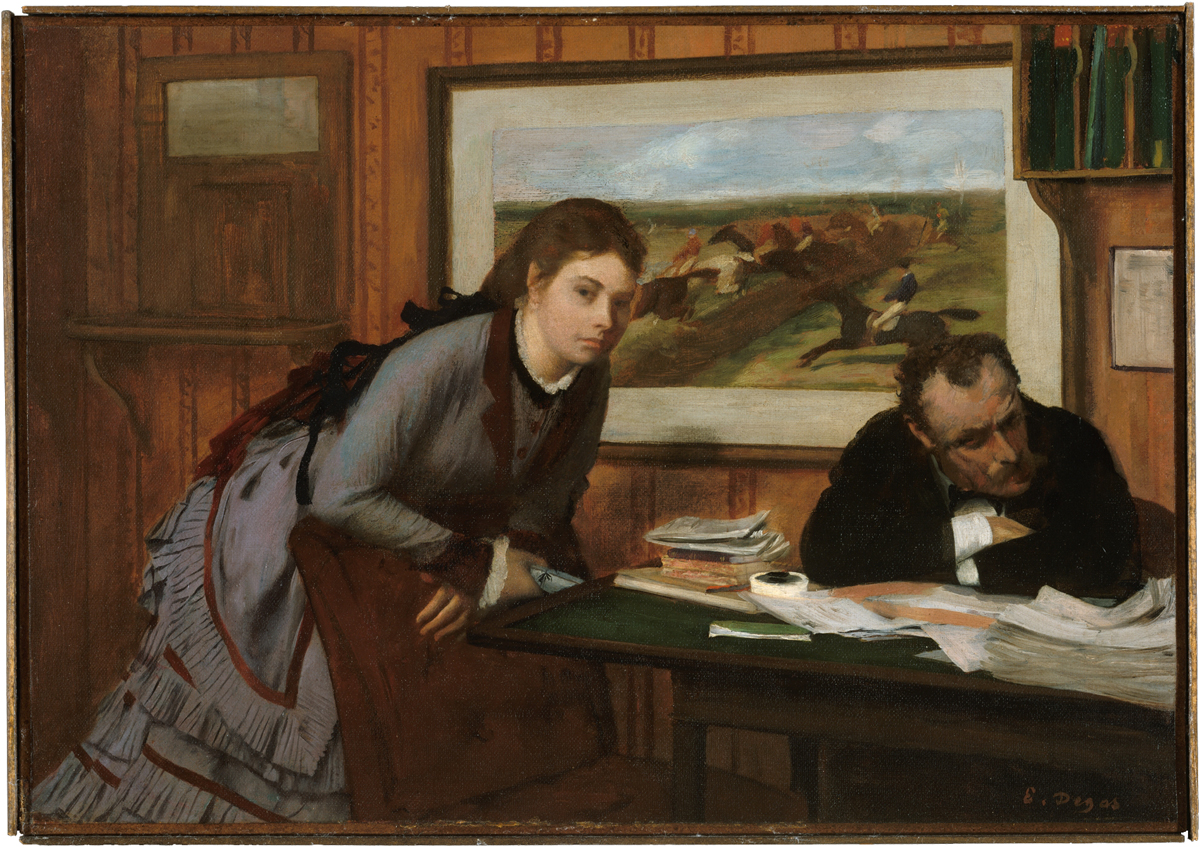

![]()

My vision of Seymour Glass flew in the face of Salinger’s. I was a hundred times more precocious, with my thick round glasses and disorderly lops of curly brown hair. In my little ascots and patterned suits, the only thing I had in common with Salinger’s Glass was our polka-dotted idealism.

By rewriting my identity, and my personal history by extension, I had hoped to confirm the rightness of my mother’s words all those years ago—that greater opportunity might knock on the door of the “better” half of me—and amazingly, it did. I had no way to tell if in my thrifted duds, I’d have had the same good fortune going by the name Ricardo, but I was sure that becoming Seymour had made the difference. As if ticking off the boxes of a best case scenario checklist, my flamboyant boss invited me to Fashion Week.

At the time, Fashion Week was kicked off by a citywide event called Fashion’s Night Out, during which fashion devotees flitted from store to store for an evening of style-oriented fanfare. I wore my brocade suit and met my boss at the Manolo Blahnik boutique, where a queue of people awaited an audience with him and a famous actress. I had been at his side for all of fifteen minutes—behind him, really, while he regaled captive admirers—when I was approached by a camera crew from an entertainment news channel. Who was I wearing? an interviewer asked, holding up a microphone. Their white light flooded my eyes. My heart raced and I lied, citing Gucci as the designer of my suit. The rest of the night I felt like a true somebody—Seymour Glass alongside his famous fashion editor friend, in head-to-toe Gucci—I almost believed it myself, and as we rode around in a black Escalade from one event to the next, flitting between conversations, I made up more lies to keep up with my own ruse: “Oh sure, I’ve met Donatella.” “Love Cannes, but I prefer when the festival has passed.” Later that week, backstage at her own show, Diane Von Furstenberg asked me if we’d met before. I laughed and assured her, yes, we’ve met—a couple times, in fact.

High off my own fantastic vision of myself, I continued going to fashionable parties in the weeks that followed. I emphasized my Yale pedigree at every opportunity, while implying that as a child I had traveled far and wide—even though, really, I had only been as far as Disney World. Although people were often intrigued by my name, nobody recognized its literary origin. If I had called myself Balenciaga, I might have received a few raised eyebrows, but in this world, evidently, Salinger was of little consequence. I didn’t have qualms about misrepresenting myself—everybody did it to some extent, didn’t they? And if I wasn’t hurting anyone, why should I tell the truth, when I was convinced the truth would hurt me?

I told myself that other people had done nothing to deserve the advantages that mere birth had ensured them. I was simply leveling the playing field; and all the while, writing everything down. As a person with terrible memory, I’d kept a pocket notebook for much of my life, a kind of shorthand diary—now I was racing through one notebook after another, taking notes on every fascinating detail: what people said, how they acted, where they liked to eat and party and go on vacation. Provided I could remember long enough to escape into the nearest bathroom, I tried my best to take down entire conversations. I was enthralled.

I should have exercised some restraint with my new persona at the office. Instead, my outfits got more daring. Inspired by Andreja Pejic, the trans model who described herself as living “between genders,” I started wearing women’s shoes—chunky heeled boots with a pointed toe. That, I’m sure, was the moment I crossed the line—although I had no idea until it was too late. In the footsteps of Caitlyn Jenner, wearing heels as a man may seem anticlimactic, but at the time, amid turmoil over same-sex marriage and the military’s “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, it was evidently too bold an assault on convention for my cubicle-bound coworkers, who had been observing my escapades from afar, unamused.

They didn’t need an official reason to dismiss me. The phrase that later haunted me was “making a spectacle of yourself,” paired with something about how people didn’t work for years in the “acceptable” fashion, only for me, an intern, to click-clack around like I belonged there.

My loss made for an unceremonious fall from grace. The first stage was denial—shock and awe, really—followed by anger in the form of a fierce, self-righteous determination to “make it” elsewhere, and show those who’d rejected me, eventually, what a mistake they had made. I applied to dozens of internships at magazines across Manhattan—only to be met with silence, and realize just how rare the opportunity I’d let slip through my fingers had been.

Like a comet with a brief blaze of a career that had been knocked off course, I floated aimlessly, my ambition replaced with dread, self-doubt, and the reversion to my lifelong anxiety, that without illumination from some greater sun to validate me—a fancy college, fancy job, fancy name—I was myself a black hole, a nobody.

In naming myself for a suicidal war veteran with PTSD, I’d evidently written myself into a morbid line of some divine foretelling. And after several bleak weeks, I suddenly had more in common with Salinger’s tortured Seymour than I’d thought.

Depression had reared its head before—in youth, I was subject to the pressures of my own angry ambitions—but even at its worst, things had never seem so bleak. To plug up the unrest that had erupted in me, I was going out every night, drinking to excess—a vice which in my college days could be justified by a jubilant precedent, but which now had become a self-destructive recourse. One late evening—it must have been two or three in the morning—my reckless misery reached a drunken fever pitch, led me staggering alone through Central Park.

Who the hell was I? What was I even trying to accomplish? I felt like a bananafish, swimming deeper and deeper into a hole I could never leave. Salinger’s Seymour had fully possessed me.

Certain of what I should do next, I ended up on a tree-lined street on the Upper East Side, and deciding on the tallest apartment building there, passed through the doors. The whole place seemed to sway beneath my feet.

Marble floors. White molding. The glint of gold fixtures as I rushed toward the nearest elevator.

I would press the ^ button—travel up, up, up. And I would jump, goddamnit. Give up on trying to make it, or be a somebody.

“Excuse me!”

As the walls appeared to flex, I still remember rooting my gaze to his white gloved hands—“Who are you here to see?” the doorman asked.

I was there to see nobody, of course. I must have stumbled toward him—no doubt with a glazed, pathetic look—because he righted me with both hands, and offered to call me a cab. If I’d made it to the roof, I would have most likely collapsed into a self-pitying heap, too sad and scared to jump, and woken up with my breath steeped in whiskey and self-loathing. Instead, after the Seymour Glass-iest moment of my life, I returned to my apartment and wrote this sentence: “With all the tall buildings everywhere, you’d think it would be easier to kill yourself in New York City.”

That same week I got offered a job at another magazine, and three years and many sentences later, that first sentence became the opening line of my first novel, An Innocent Fashion.

“They want to publish your book,” my agent said over the phone, “on the condition that it’s under your name—not Seymour Glass.”

By that point, I was exhausted from teetering constantly on the tightrope that was Seymour Glass. It was like a work of performance art that had gone on too long, for which the consequence of one wrong move was a long drop and a hard fall. Furthermore, I had long since started to be unsure which self was the “true” one, Ricardo or Seymour. And after spending so much time surrounded by the people I’d longed to be like, I couldn’t even remember why I’d wanted to be one of them.

And so Seymour Glass died once more.

R. J. Hernández is the author of An Innocent Fashion.